This week saw the release of our latest pre-print on bioRxiv! Titled Silent recognition of flagellins from human gut commensal bacteria by Toll-like receptor 5, this work was led by postdoc Sara Clasen and describes a mechanism for how the human immune system can tolerate commensal microbes.

Our innate immune system evolved to defend us against pathogens we’ve never encountered before. This remarkable ability is carried out by receptors that bind molecules made by microbes that are both highly conserved and wide-spread. Following detection, the receptors turn on pro-inflammatory pathways that eventually lead to adaptive immune responses. But how do non-pathogens, especially the trillions of beneficial microbes that inhabit our gut, avoid triggering these receptors?

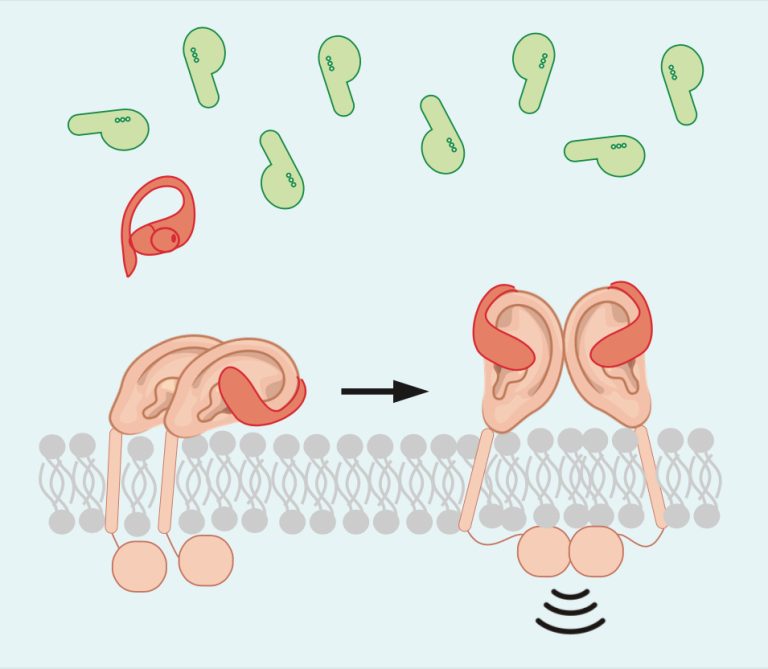

To address this question, we looked at how the innate immune receptor Toll-like receptor 5 (TLR5) interacts with its ligand, the bacterial protein flagellin. Flagellin is the main subunit of flagellum, a whip-like structure that bacteria use to move. Both pathogenic and beneficial bacteria produce flagellin, and the region that TLR5 recognizes is identical in both as well. In humans, the dominant producers of flagellin are members of the Lachnospiraceae family. These taxa are considered markers of health, in part because they provide fuel for the human host in the form of butyrate.

We tested approximately 125 flagellins commonly found in the human gut – most made by Lachnospiraceae – for their ability to be recognized by TLR5 (i.e. bind) and to stimulate host responses. To our great surprise, many of the flagellins from beneficial taxa bind TLR5 but do not provoke a response. We called these ligands “silent flagellins.”

To understand how silent flagellins avoid activating TLR5, we compared them to the stimulatory flagellin FliC from the human pathogen Salmonella. While silent flagellins bind TLR5 at a single site, we determined that FliC binds TLR5 at two separate locations. This extra binding site enables FliC to activate TLR5 at very low concentrations. When silent flagellins are provided with this extra binding site, their ability to stimulate TLR5 increases by orders of magnitude.

Our work shows that, while innate immune receptors evolved to recognize common microbial ligands, additional layers of regulation exist to prevent unnecessary responses to beneficial microbiota. Interestingly, some individuals with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) have adaptive immune responses to flagellins from Lachnospiraceae, including silent flagellins. Whether these immune responses are a consequence or a driver of IBD remains unclear. We found that silent flagellins are substantially depleted from Westernised populations, a group with increased incidence of IBD. Future studies will examine the role of altered flagellin-TLR5 interactions in both healthy and disease states.

Clasen, SJ., Bell, MEW., Lee, D-H., Henseler, ZM., Borbón, A., de la Cuesta-Zuluaga, J., Parys, K., Zou, J., Youngblut, ND., Gewirtz, AT., Belkhadir, Y., Ley, RE. 2022. Silent recognition of flagellins from human gut commensal bacteria by Toll-like receptor 5. bioRxiv: https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.12.488020